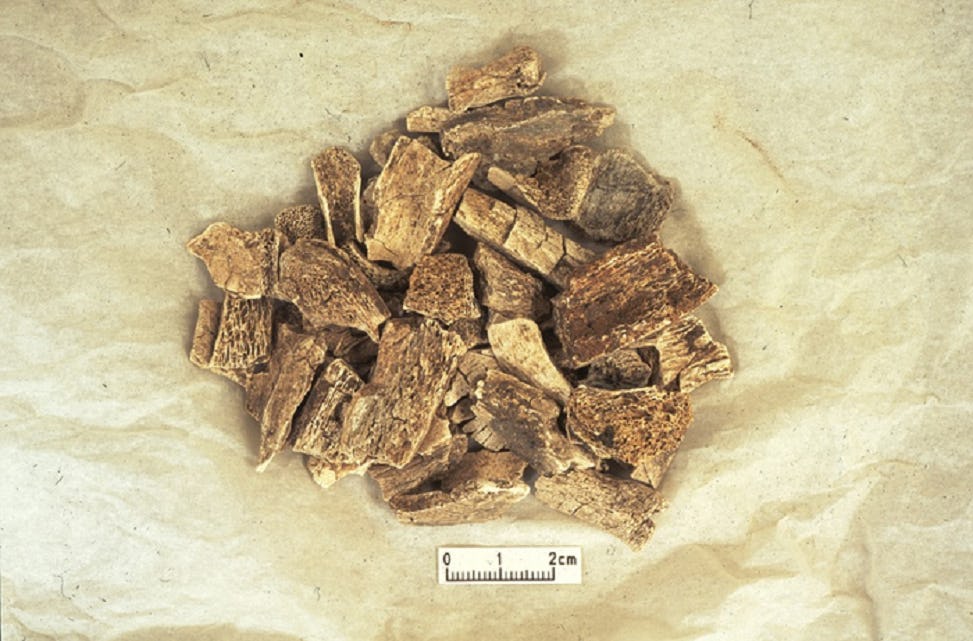

Cremation leaves behind bone fragments like these, which can still reveal information about their geographic origin, if not much else.Julian Richards, University of York

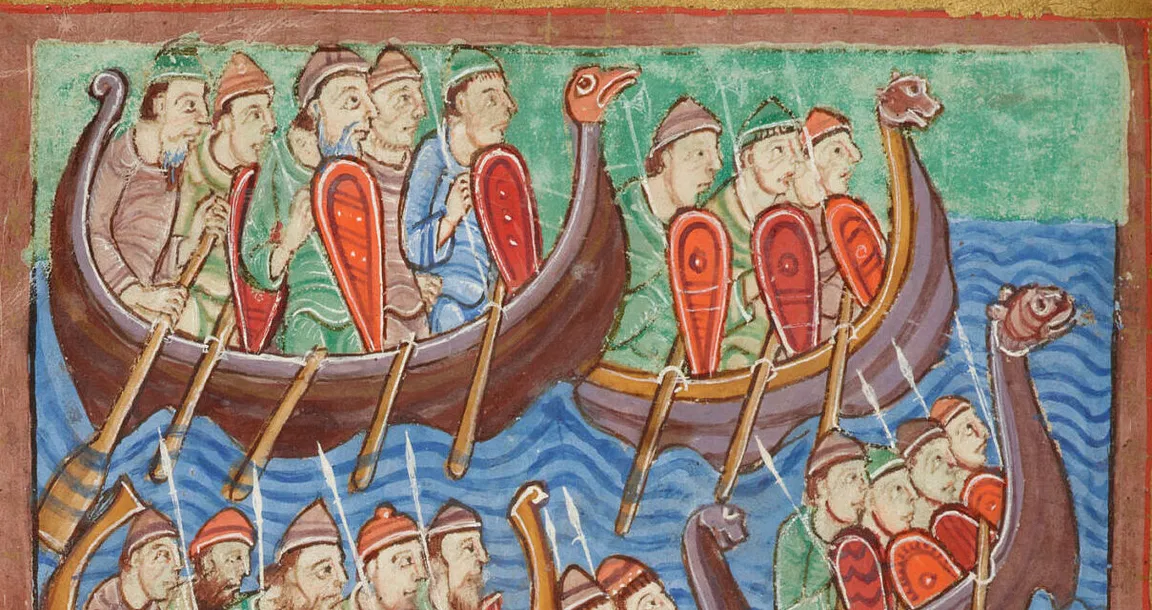

The bones of one dead warrior and their animals may shed new light on the Viking Great Army’s logistics.

When the army of (mostly) Scandinavian warriors landed in East Anglia in 865 CE, they came to plunder — and they were equally happy to fight or to extort the locals. The king of East Anglia, Edmund the Martyr, apparently gave the Viking Great Army horses in return for not having to fight the Vikings, and unleashing them on neighboring, rival kingdoms like Mercia and Wessex. Elsewhere, the Vikings were said to steal horses and whatever else they wanted.

Based on historical descriptions like the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, it sounds like the Viking Great Army’s approach to logistical planning was “we’ll just steal it when we get there.” But recent archaeological evidence suggests that at least some Vikings brought animals like horses, dogs, and maybe even pigs with them on their campaign to Britain.

Durham University archaeologist Tessi Löffelmann and her colleagues published their findings in a recent paper in the journal PLOS ONE.

What’s new — Wherever you go in the world, the bedrock beneath your feet has a particular ratio of different isotopes of the element strontium. That isotopic ratio gives the place a chemical fingerprint that’s shared by plants that grow in the soil, animals that eat the plants and drink the water, and other animals that eat those animals. Once it’s in the body, strontium can fill in for calcium in your bones, so that if you’ve in a place long enough, its geology becomes part of your bones.

Read the rest of this article...